CONVERSE - Verda Byrd describes the yield of her adoption story and search for her biological parents as a love story.

Love may not be the most fruitful word to describe her experience but this is Byrd's story and she's sticking to it.

"Am I black or white?" She asked. "It's really doesn't matter to me because I'm not changing."

The 75-year-old Converse woman discovered she had a white mother and father. Byrd had been raised as African-American. She said for 70 years she thought she was black.

"I didn't know what I was, " She said.

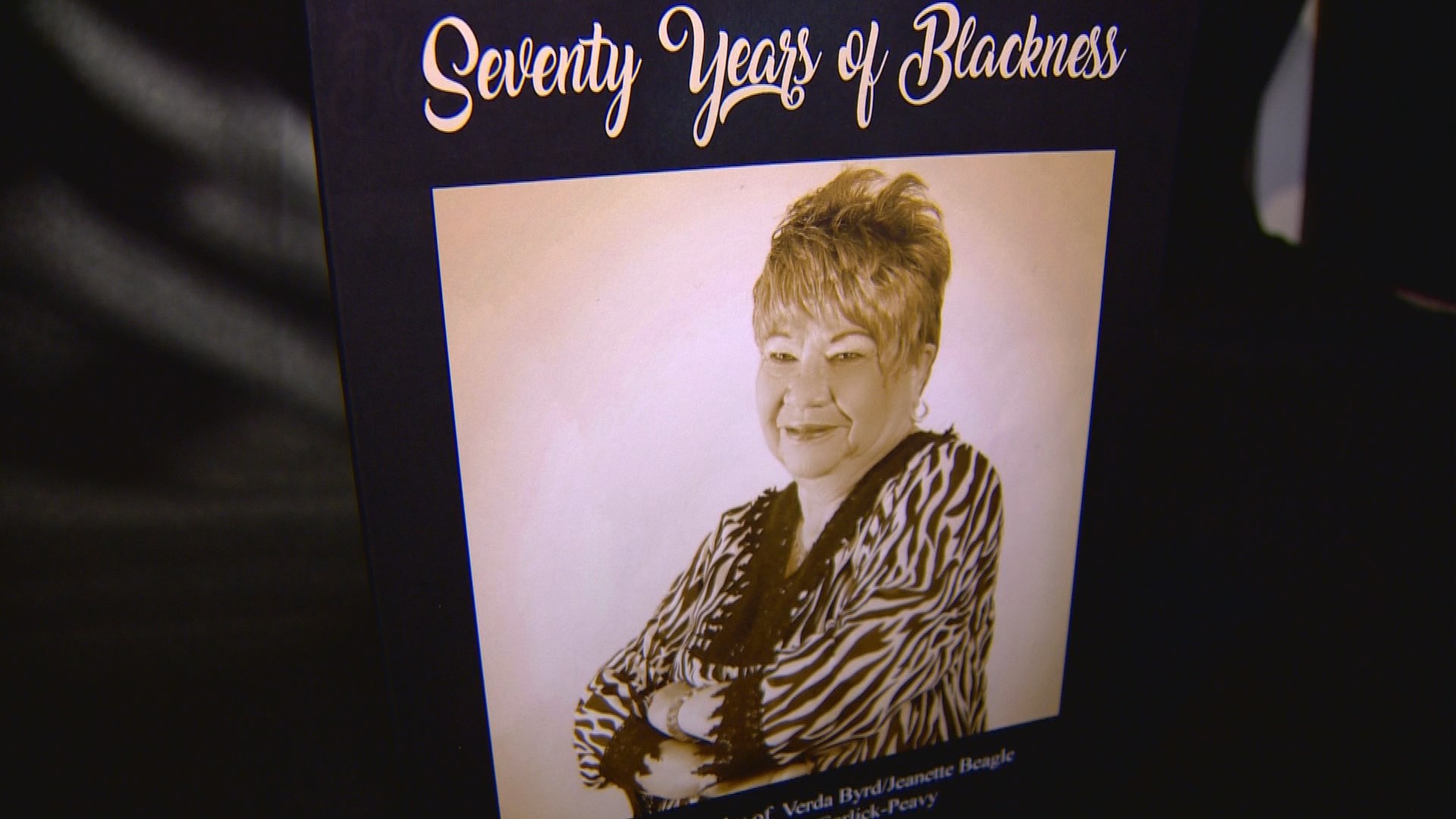

Byrd tells her story through Joyce Garlick-Peavy in the book Seventy Years of Blackness. Prior to that Byrd's story set the internet and newscast on fire in 2015.

In a 2015 interview with KENS 5, the wife and mother of one said she never questioned her ethnicity.

"It was never told to me that I was white," she said.

According to Missouri court documents, Daisy and Earl Beagle were Byrd's biological parents. They were an economically challenged family with five children in the 1940s.

Byrd said Earl deserted his family in 1943. She was five months old when her 27-year-old mother went looking for work. Daisy fell 30 feet to the ground in a trolley accident. The struggling mother was critically injured.

The state took Byrd and her siblings into their care. Daisy got all of her children back after she recovered from her injuries except baby Jeanette.

Jeanette was on her way to being adopted by Ray and Edwinna Wagner. In fact, the couple changed the child's name to Verda Ann Wagner.

Ray was a college educated railroad porter who earned $250 a month. His salary is the equivalent of making more than $42,500 annually in 2018.

MH: Do you regret not having a relationship with them?

VB: With Daisy and Earl?

MH: Right.

VB: No, I don't regret. Because the way I understand it now is they probably wouldn't have been able to provide the good life that I've had.

Byrd was raised as the Wagner's only child. Educationally, financially and culturally she believes her life couldn't be matched by the troublesome life of the Beagles.

Earl enlisted in the Army. Daisy, according to Byrd, sought financial stability by any means necessary. In fact, the couple's stressful marriage brought on questions of fidelity.

Fidelity became a focus when the court of public opinion weighed in on Byrd's ethnicity. She's viewed as a fair-skinned African-American woman.

VB: Maybe Daisy had other boyfriends. Maybe Daisy had...which I do know for a fact...she married two or three other men while she was still legally married to Earl. So maybe when mothers are desperate to provide for the children that they have sometimes they might and often do things that are not acceptable.

MH: So there's a chance that while Daisy is your biological mother that your father may be...

VB: At this point in my life, yes I have received information and I have been told sometimes Daisy might not have been the most upright mother.

Her biological mother had five more children. Byrd said on paper Earl Beagle was their father too.

The shocking revelation of her birth parents didn't generate anytime to reconnect. Earl and Daisy were dead by the time Byrd finished her research.

"Christmas 2014 I went to Daisy Beagle's Grave in Dallas," She said. "And all I said to her is Daisy I'm home. I've been gone all these years. And, I'm here to wish you a Merry Christmas."

She never refers to the Beagles as mother and father. The Wagners hold that honor in her life. They are dead too.

"I don't call anybody mama and daddy if I don't know them. If they didn't raise me," she said.

Byrd did have a highly publicized reunion with her sisters Sybil Panko, Debbie Romero and Kathyrn Gutierrez in 2014.

"We are Daisy's girls," she said at the time.

According to Byrd, Panko used the N-word. The two sisters argued and stopped speaking the same year they reunited. Panko died in September 2016. She left a request for Byrd not to attend her funeral in Florida.

Byrd said her other sister stopped talking with her after Panko's death. She was hurt.

"What did I do?? I found you," she said. "You are my sisters."

Byrd's book is driven by the belief she was wrongfully adopted and robbed of her white heritage. She recalls after discovering her birth mother was white being at the doctor. There she sat trying to fill out a medical form when the biggest question of her life was printed on the paper. What was her race?

"What box do I check?" She asked.

The outspoken adoptee chose to check other.

"Anyone who wants to know - ask me," she said.

Byrd's book is available on Amazon and Barnes & Noble. Autographed copies can be ordered at 210-326-8986, trancle@sbcglobal.net or verdabyrd@hotmail.com. She plans to donate part of the proceeds to Texas Child Protective Services for foster children.