Alcolu, SC(WLTX)-- Lawyers arguing for George Stinney, Jr.'s innocence willbring their case before a judge Tuesday morning.

George Stinney, Jr. was executed in South Carolina when he was just 14-years-old for the murders of two young girls in March 1944.

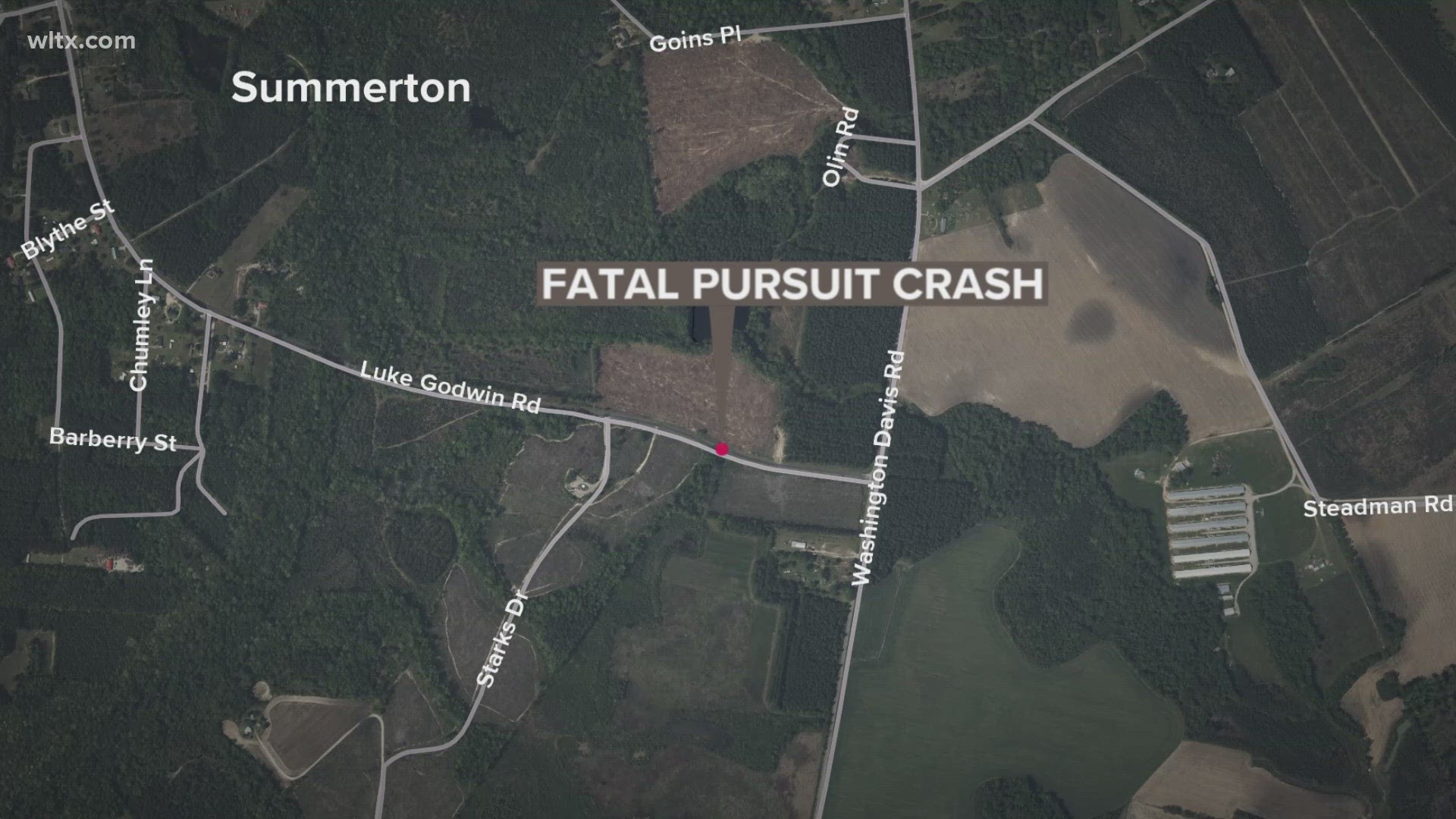

It happened in Alcolu, located just outside of Manning in Clarendon County.

The girls were white and Stinney, Jr. was black.

Stinney, Jr.'s supporters believe the young man was forced to confess to the murders, and now they want his conviction thrown out. His 77-year-old sister, Amie Ruffner, says her brother was innocent, and spoke only to News19 on Monday ahead of the court date.

Ruffner admits she and her brother saw the girls the day they died after they stopped by to talk about finding some flowers.

However, she said the girls were very much alive when they left, and that she and her brother had to tend to the family cow.

"I never saw my brother alive again from that day they took him out of our yard and out the house," Ruffner said.

It's the first time in 70 years Ruffner is breaking her silence, professing the innocence of her older brother.

Ruffner said she knows her brother is innocent because she never left his side after the girls, Mary Emma Thames, 7, and Betty June Binnicker, 11, asked them where they could find flowers as they tended to a family cow near a set of railroad tracks near their home.

"They said 'could you tell us where we could find some may pops,' Ruffner recalled. "We said 'no,' and they went on about their business."

The girls were later found in a water-logged ditch in a field near the Baptist Church on Greenhill Church Rd.

"Two black cars pulled up in front of our house, and they went in our back door and they came out," Ruffner said, recalling the day George and her older, brother, Johny were put in handcuffs and led from their home. Only later did they let Johny Stinney go, she said, leaving George Stinney, Jr. to face police questioning.

At the time, both her parents, George Stinney, Sr. and Amie Stinney were away from the home, she said.

"(The police) were looking for someone to blame it on, so they used my brother as a scapegoat," Ruffner said.

A coroner's inquest and subsequent grand jury indictment for the murder of Thames led Stinney, Jr. to face trial for the murder at the age of 14.

Records show a state witness testifying to a confession Stinney, Jr. made, though no record of that confession has surfaced.

Stinney, Jr. was tried and convicted all in the same day. His sentence was to face an electrocution less than 90 days after the girls' bodies were discovered, despite dozens of letters written to then South Carolina Gov. Olin Johnston.

Johnston believed Stinney, Jr. committed the crime to rape one of the girls' dead bodies, though an examination report of the girls' bodies claims different.

An unmarked grave has now become George Stinney, Jr.'s final resting place.

"If we had allowed a stone to be there, and someone would have found out where my brother was, they probably would have dug his grave up and thrown him to the wolves," Ruffner said.

Attorneys arguing the case Tuesday believe there are a number of reasons Stinney, Jr. should be granted a new trial.

"There's an individual who is the foreman of the jury on the coroner's inquest," said Matt Burgess, an attorney at the law firm of Coffey, Chandler and McKenzie, the attorneys who will make their case Tuesday morning. "He'd signed as a witness, also, on the indictment forms. He was a witness of the grand jury."

Burgess said the same man was also a member of the search party that found the girls bodies.

"For one person to have been on so many steps of that procedural process certainly tends to suggest a violation of George Stinney's due process rights," Burgess said.

After her brother's arrest, Ruffner said the family was run out of town so they moved to Sumter.

Now, some 70 years after burying her brother, she refuses to return to Alcolu, but says she holds no anger in her heart.

"Even if you think I'm wrong," Ruffner said, "my brother did not do it, and I hate no man.

Instead, she is determined to look forward while hoping for the best.

The hearing will take place at the Sumter County Courthouse.